To raze or not to raze that old grain elevator

By Joe Kimball

Published Feb 25, 2002: Pioneer Press newspaper

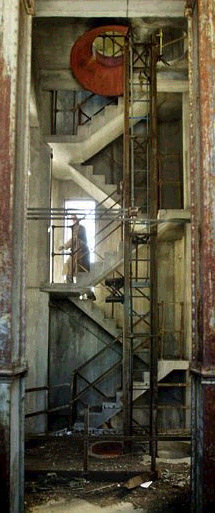

The old grain elevator on the banks of the Mississippi River is an unlikely gem in downtown St. Paul's changing riverfront. Broken windows, gaping holes and a desolate platform hanging over the river make it a likely candidate for the wrecking ball. Grain bins and chutes rust away in the upper levels of the concrete head house, while the adjoining brick sack house is visited only by pigeons and vagrants.

Yet for social and historic reasons, there's a movement afoot to save the relic. A design competition, sponsored by the St. Paul Riverfront Corporation, has begun in an attempt to find ways to reuse the nearly 75-year-old structure. Four winning concepts will each earn $5,000, although there's no guarantee that the city of St. Paul, which owns the property, will actually implement any of the designs. Still, it's a chance -- probably the last chance -- to find a creative, affordable use for the buildings.

City Council Member Chris Coleman hopes it works. "It's got the finest view in St. Paul," said Coleman, who represents the area and who will be part of the jury that selects the winning designs. "And it's built out over the Mississippi; you could never get permission to build something like that again, so it's a great opportunity."

The elevator buildings were built between 1927 and 1931 as part of the Equity Cooperative Exchange (later it was Harvest States Cooperative). Grain was stored in dozens of nearby silos, then transferred through a chute stretching over the old Shepard Road into the concrete head house. From there it was transferred to barges on the river below. Some grain also was stored in sacks and kept in the adjacent brick sack house.

City officials have been considering the elevator's fate since 1989, when they began a major effort to clean up the riverfront area known as the Upper Landing. Dozens of grain silos were removed, but the cleanup effort ended before permits were obtained to demolish the elevator structures. No official action was taken until an ambitious housing and commercial project on 17 riverfront acres surrounding the buildings came together in 2000. National housing developer Centex took a long look at incorporating the head house into its $170 million urban village, but ultimately decided it wasn't feasible.

Now the city is using the money that had been set aside for demolition of the buildings to pay for the design contest; Centex will pay for demolition if no designs are deemed feasible.

Despite their lack of outward appeal, the buildings have historic significance, supporters say. "It's really the last connection to St. Paul's history as a port city," said John Anfinson, historian for the National Park Service. "It's right on the river, and if we could find a way to restore and reuse it, we'll have a portal to the river that doesn't exist anywhere else in downtown St. Paul."

The elevator was built just as Congress was considering a plan to deepen the Mississippi channel with dredging and dams, to improve navigation and recapture some of the transportation business that had, by then, been largely taken over by the railroads. To justify the huge expense, proponents wanted river cities to prove that they'd use the river for traffic. "So the elevator was built in St. Paul to demonstrate that it could have a modern connection to the river," Anfinson said. He said the elevator also is a remnant of a profound change in society.

The old elevator and adjoining structures dominated a key part of the river in July 1939.

The buildings were built between 1927 and 1931.

The Equity Cooperative Exchange, which built the elevator in St. Paul, was made up of farmers organized to fight the big grain merchants of Minneapolis, who controlled much of the grain marketing in the Midwest. That was a radical position at the time.

The elevator saw its heyday in the 1950s, when nearly 100 silos lined the surrounding area on the levee. But transportation patterns changed again and now grain is shipped from other ports, leaving the elevator an empty hull. Someone startled by the ubiquitous pigeons has written on a top-floor wall: "Beware, attack birds on duty."

Becca Hine, president of the West 7th/Fort Road Federation, said many nearby residents would like to see the elevator restored because of its historic significance. "It's an icon on the river. It speaks to the use of the river," she said. Hine was on a committee that came up with dozens of ways to save the building, including a restaurant, museum, climbing wall, bike shop or a rental shop for in-line skates.

Conversion to housing also has been considered, mainly because of the unparalleled views of downtown, the river and its bluffs on both sides. But studies indicate that the cost would be prohibitive. Those entering the design competition must consider the potential costs of their plans and they must consider the flooding potential. Water rises about 3 feet inside the building during major floods, said Gregory Page of the Riverfront Corporation. Parking issues must also be addressed.

But those involved in the contest eagerly await the designs -- which are expected to be submitted from around the world -- and hope some magical idea will emerge to save the head house. "This is such a unique opportunity," Council Member Coleman said. "I hope it will inspire peoples' imaginations."